Complete Guide to VFD Efficiency, Energy Savings, and ROI

Electric motors are the world’s largest consumer of energy. Estimates range from 40% to 53% of the world’s electricity is used by electric motors, with the number growing as the world electrifies.

Making AC motors more efficient is good for both your wallet and the environment, but we’re reaching a point where even highly advanced motors like the ABB SynRM motor have picked up all the low-hanging fruit for efficiency. The easiest way to pick up more efficiency is usually not through the motor, but in how you control the motor. This is where variable frequency drives come into play.

As efficiency becomes a focus, VFDs are going to become more common in every application. To help explain why, we’re going to dive into the world of energy, exploring how VFDs improve efficiency (especially when affinity laws are relevant), what losses you encounter with a VFD, and how to calculate your return on investment (ROI) and payback period when looking at adding a VFD.

How Variable Frequency Drives Improve Efficiency

The actual topology of a VFD isn’t crucial when you’re trying to understand variable frequency drive efficiency. If you want to know, you can read about how a VFD works here. Otherwise, the important thing to understand is how the VFD affects the motor.

Without a VFD, an AC induction motor runs constantly at full speed. When a VFD is added, you can now slow down the motor by adjusting the frequency the motor thinks it sees. Why does slowing down the motor help? When the motor runs slower, it uses less energy.

An easy way to picture this is with a pump. Imagine that you have a motor running a pump to move 100GPM (gallons per minute) when you only need 50. Without a VFD, you run the motor at full speed, using the power to move that much water, and then you restrict flow somewhere else through something like a valve. Without much technical knowledge, this process already sounds inefficient to most, like driving a car with the gas pedal all the way down while also using the brakes.

What if you could run the motor slower and only pump 50GPM? With a VFD, you can. Now the motor doesn’t work as hard and uses less electricity, plus you get to save mechanical stress on pumps, pipes, and valves in the rest of your system.

Initially this concept seems great, you’re saving half the energy by running half as fast. That’s where the real power of a VFD comes into play. With pumps and fans, you actually save even more than that.

How Affinity Laws Save Energy

Affinity laws are one of the wonders of the modern electrical world. When you’re dealing with centrifugal loads like fans and many pumps, you have a few terms that are important to know.

- Speed (usually “N”) - Speed is how fast something moves. This is the simplest to understand and is usually measured by the revolutions per minute (RPM) on rotating assets like pumps, fans, or motors.

- Flow (usually “Q”) - How much is moved over time. This is likely fluid or air depending on your system. This is the volume of what you’re moving. Think of terms like gallons per minute (GPM) or liters per second for fluid and cubic feet per minute (CFM) for fans.

- Pressure (usually “H”) - How much force is generated to move the fluid or air. This is the resistance to the flow. It’s measured by force per area, like pounds per square inch (PSI) or height of fluid (feet/meters of head).

- Power (usually “P”) - How much energy is used. This is measured in standardized units like horsepower (HP) or kilowatts (kW).

Let’s pause here to talk about the symbol ∝. This symbol means “proportional to.” It’s similar to the equal sign, but not the same. Speed is not technically equal to flow, but it is proportional, meaning as one value increases, the other increases at the same rate. Anywhere you see the ∝ symbol, just substitute that phrase (“proportional to”) in your head.

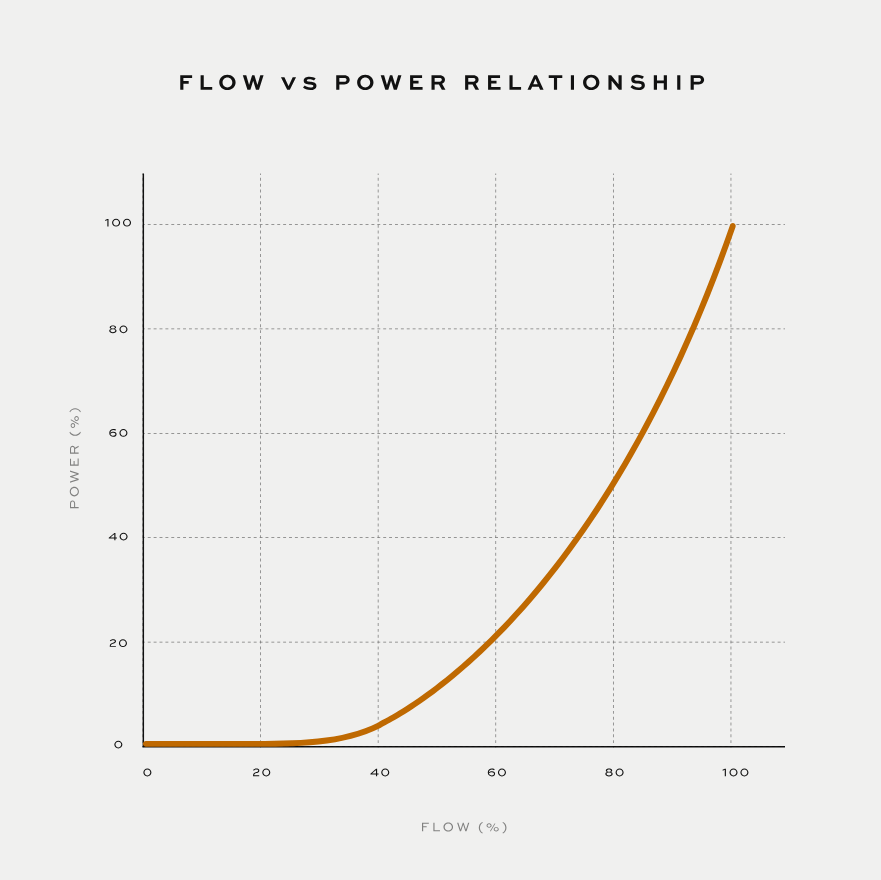

Back to affinity laws, the first complication to the relationship between these terms is that flow isn’t linear with pressure, it’s quadratic. That means it’s squared, with pressure ∝ flow2 as the equation, also shown as H ∝ Q2 or N2. That means when pressure increases, flow is increasing at a faster rate, not the same rate.

Power is flow multiplied by pressure. When you look at the equation, you now have P ∝ Q x Q2 or N x N2 which can also be shown as P ∝ Q3 or N3. Similar to flow, this means that as power increases, flow is increasing at an even faster rate.

With all the math laid out, let’s take a step back and look at what that means. For any speed or flow you need, it’s related to the power required by that cubic function.

Let’s go back to our example above. If full speed is 100GPM but it’s a centrifugal pump, when you reduce the speed by half, you don’t reduce the power (or energy needed) by half, you reduce it by much more. Rather than dividing by 2, you take your new speed to the power of 3. Your new speed is 0.5 of full speed, so your power is 0.53 or 0.125.

The takeaway? You get half the flow of water but only spend 12.5% of the energy. Your 50% reduction in speed just saved you 87.5% of the electricity.

This idea isn’t intuitive to most people, so imagine walking up a slope. Walking on a slight incline adds a little bit of work, but a steep slope becomes so intense that the effort seems completely unrelated - at a certain point you’re putting the effort of sprinting just to keep moving at a slow speed.

VFD Efficiency Losses

VFDs have the potential to save a lot of energy, but they’re not a perfectly efficient component. There are losses within the VFD itself. A standard VFD is typically somewhere between 96% and 97% efficiency. That means there’s 3-4% loss for all the power you feed through a VFD to a motor.

If you aren’t going to slow your motor down at all, these losses are unnecessary. Although there may be mechanical reasons to use a VFD (such as reducing inrush current damage to your motor), you are actually making your system less efficient.

The reason that VFDs make sense from an efficiency standpoint is that they usually save more energy than they lose. If you’re saving 87.5% of the energy from the example above, a 3% loss from the drive’s internal components is a small price to pay. Even if the loss is small, it’s important to consider all conditions when calculating your payback.

While you’re at it, consider other things that may affect efficiency. Harmonics, power quality filters, additional cabling, and any other components will reduce efficiency and should be considered.

Calculating VFD ROI and Payback Period

As you consider a VFD for increased efficiency, the question of payback comes up. You weigh initial costs and VFD losses against the efficiency gains. To determine payback, there are two steps. First, determine the annual energy savings, then use that to determine your payback period or ROI. It’s a simple concept to explain, but many variables can factor in.

Among these variables is the fact that many loads are variable. If you have PID control, the VFD itself is adjusting speed to maintain the pressure. For any of these calculations, use either an average or your best estimate of what the average will be.

There are also many potential efficiency losses, from cable to filters, all with their approximate efficiency. ROI and payback are useful terms, but are best used as an approximation, especially when forecasting.

Annual Energy Savings

To find annual energy savings, start with the total energy savings you’re introducing and remove the total energy losses.

Annual Energy Savings = Total New Energy Savings - Total New Energy Losses

Let’s take an example of a VFD on a 100kW (about 135HP) motor for a centrifugal pump that is used 5,000 hours per year out of a possible 8,760 hours. Let’s also say that the average actual flow needed is 70% of the full potential, which corresponds to ~70% speed. Annually the system will use 500,000 kilowatt hours (kWh), calculated from the 5,000 hours multiplied by 100kW.

Using the affinity law math, this 70% speed uses 34.3% of the full load power, meaning we save 65.7% of our energy. 500,000kWh now turns into only 171,500kWh. Our new energy savings total 328,500kWh.

For simplicity, we’ll ignore all losses except the VFD itself in this example. At 96% efficiency, the VFD consumes more than 171,500kWh to be able to output that amount. The math on that is to divide the new kWh by the VFD efficiency, or 171,500 / 0.96 which gives us 178,645. The VFD requires that we supply an additional 7,145kWh throughout the year because of efficiency losses.

As a side note, this means that our VFD savings moved from 65.7% to 64.3% which means the VFD inefficiency adds 1.43% of the full-load power back into the calculation.

Let’s plug everything into the formula above.

Annual Energy Savings = 328,500kWh - 7,145kWh = 321,355kWh

This number is helpful, but so far we only know the measurement of the electricity we didn’t use. Let’s turn the savings into a dollar amount.

According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), the average commercial and industrial utility rate across the United States is between $0.09/kWh to $0.14/kWh. Just for reference, the full range of average rates is $0.0628/kWh in Louisiana to $0.35/kWh in Hawaii.

The math here is simple. Take the electrical rate multiplied by the total kilowatt hours. We’ll take a simple number in the lower end of the average range to be conservative, $0.10/kWh. You would take your actual rate from the utility. In our example, the annual energy savings in this system are about $32,135.50.

ROI and Payback Period

Return on investment (ROI) and the payback period are where the financial benefits of VFD energy cost reduction come into play. Just like with annual energy savings, the formula is simple, but the variables can make it more complicated.

Payback Period = Initial Cost / Annual Energy Savings

The initial cost has many elements that are easy to identify. The purchase price of the VFD, wire, filters, or any other components are likely combined into a purchase order, invoice, or receipt. If installation and commissioning were hired out, then there’s also a record of that. If not, you may need to track hours, estimated or actual, for those services, as well as your internal labor rate.

Look at the cost of downtime during installation or any other hidden factors. When you’ve done this, total all costs.

Let’s use an example VFD from VFDs.com, as well as a day of field labor for installation and commissioning. The G540-01800UL-03 would be a great drive for a motor this size and currently sells for a little under $7,000. Low voltage VFD labor varies based on location, but to combine both installation and commissioning, cost could be estimated at $1,500. For simplicity, we’ll ignore downtime and other costs, but make sure you include it in your calculations.

Your total initial cost is $8,500. Plug that and the annual energy savings from above into the formula to find your payback period.

Payback Period = $8,500 / $32,135.50 = 0.26 of a year (or just over three months)

In this case, your payback period is three months. If you need to find your annual return on investment, just flip those numbers in the equation (annual energy savings divided by initial cost), and in that year your ROI was 378%, which is one of the best investments you could make for a facility.

But what if you were to reduce your speed more or less, or go with a more expensive VFD package? What if you were to install a VFD but not vary the speed at all? Feel free to run the numbers yourself, but let’s summarize this same situation with different variables.

50% speed = 2 ½ months (511% annual ROI)

90% speed = 8 ½ months (142% annual ROI)

100% speed = $2,083 annual increase in energy costs (negative ROI)

70% speed with VFD panel* = 10 months (119% annual ROI)

*Includes a passive harmonic filter; VFD cost is now approximately $25,000 instead of $7,000; also note the harmonic filter is typically about 97% efficient, which was addd into this calculation and slightly extends the payback period while solving harmonic distortion.

The numbers for this will change based on many variables. You may have a different utility rate, VFD cost, labor costs, running hours, or needed flow. With the walkthrough, you can run the numbers yourself, plugging in your real costs and requirements.

No matter what your specific numbers are, when you need to control the speed of a centrifugal load, facilities are often surprised just how quickly a VFD can pay itself off and start saving money.

How VFDs Save Money (Other Than Efficiency)

Efficiency is a fantastic reason to get a VFD, but it’s not the only way they can save you money. Power factor can be another big cost saving. You can learn more about power factor here, but the main takeaway is that AC induction motors often have a low enough power factor that it can hurt your electrical bill.

Large numbers of inductive loads lower your power factor, which can lead to two additional costs: higher power levels delivered from the utility (that you pay for) to get you the real power you need, and a potential power factor penalty added to your bill.

Adding a VFD to a motor raises the power factor. The typical VFD has a 0.96 power factor, which is higher than the usual requirement from the utility to maintain a 0.90. While the requirement is based on the power factor of your entire facility, raising the power factor of a motor can influence that result.

VFDs can also save money on mechanical components. Like mentioned above, running motors across the line can lead to many mechanical issues, such as inrush damage to the motor, wear on mechanical components like pipes and valves, and even issues with water hammer. Using a VFD and avoiding these issues extends the life of non-electrical equipment throughout your facility.

In one case, we helped an oil & gas customer who was running full speed and pumping extra water for their process that just recirculated. All water that was used had to be treated by chemicals. By reducing the amount of water that was pumped and recirculated, the amount of chemicals used to treat the water was reduced, saving money and potential environmental exposure.

While not the main reason to buy a VFD, each of these topics can factor in the total savings in a VFD installation, decreasing the payback period and increasing the return on investment.

Calculate Your VFD Payback

Each situation is unique, and your numbers will vary. Use our payback calculator to find out how much you can save by using a VFD. If a VFD makes sense for your system, reach out to our team to start saving money today.

Frequently Asked Questions

How do VFDs save energy?

VFDs save energy by slowing an AC induction motor, reducing the energy consumed for a process. That reduced energy is electricity that doesn’t have to be used or paid for.

How much energy can a VFD save?

How much energy a VFD saves every year depends on factors like running hours, desired flow rate, and efficiency losses. Because of affinity laws, centrifugal loads can easily save more than 50% of the energy needed for full speed operation.

What are affinity laws and how do they relate to VFD savings?

Affinity laws describe the relationship between speed and power. For centrifugal loads, this is a cubic function, meaning small reductions in speed can save a lot of energy and money.

What is the ROI or payback period for a VFD?

The payback period or return on investment (ROI) for a VFD will vary based on several factors, but for centrifugal loads it can easily be within a 1 or 2 year timeframe.

How do you calculate VFD energy savings?

You need to perform two calculations to find VFD energy savings. First find your annual energy savings by taking your total new energy savings and subtracting your total new energy losses (typically due to efficiency losses). Then take your initial costs to buy and install a VFD and divide annual energy savings. The result is how many years it takes to make back the cost of the VFD. ROI is the inverse, dividing your annual savings amount by the initial costs to find the annual ROI percentage.

Are VFDs always efficient?

Modern low voltage VFDs are usually about 96% efficient. In cases where speed control of an AC motor process is needed, this efficiency loss is usually far less than other efficiency gains. When speed reduction is not needed, a VFD adds components with efficiency losses but doesn’t save any energy in the process.

Do VFDs reduce maintenance costs?

VFDs often reduce maintenance costs tied to mechanical wear, inrush current, and similar issues. VFDs themselves need maintenance and may cause issues like harmonics or dV/dt that need to be mitigated, adding some cost. In general, a VFD reduces more maintenance cost than it introduces.

Can a VFD improve power factor?

VFDs typically improve power factor on AC induction motors. Standard low voltage VFDs have a 0.96 power factor, which is higher than most AC motors.

What are typical applications for VFDs in energy savings?

While VFDs can save energy in any application, they save the most energy in applications affected by affinity laws. These are centrifugal applications like fans and centrifugal pumps.

How efficient are VFDs?

Most standard 6-pulse low voltage VFDs with an IGBT configuration are about 96-97% efficient. Advances in technology, such as the use of silicon carbide (SiC) MOSFETs can increase efficiency.

Do VFDs qualify for energy rebates or incentives?

VFDs qualify for many energy rebates and incentives. Reach out to your local VFD provider or utility to learn more. Note that utilities often require that you start the rebate process before proceeding too far down the path to specify or buy a VFD, so check early!

Do soft starters help save energy?

Soft starters do not contribute meaningfully to energy savings. They are engaged for only a short time to slowly ramp up a motor, then they enter bypass. Although some inrush current is reduced, this is not a typical source of energy. They can help reduce the peak demand needed for your facility, so they may help reduce your electrical utility rate in some cases, though not the actual energy consumption.

Can VFDs save energy on non-centrifugal loads?

Yes, VFDs save energy whenever they are reducing the speed of a process and therefore the energy needed to power that process. Although centrifugal loads have increased energy savings for speed reduction, other loads still benefit from reduced speed and lower energy costs.