What is Power Factor?

Power factor is one of those terms that gets brought up in many electrical discussions but is often misunderstood. It’s an important concept that is often costing money and causing problems without a facility understanding what is happening. We’ll cover what it is, how to calculate it, when it becomes a problem, and how to fix that problem.

What Is Power Factor?

Power factor is ultimately a measurement of how effectively a system uses electricity. It’s an issue that commercial and industrial users should worry about, but not typically something that residential users will care about. In fact, historically there have been fake “snake oil” types of scams that target residential power factor. In general, utilities will not penalize a residential user for low power factor as they are relatively minor contributors to the general utility problems.

For industrial and commercial users, power factor tells you how much of the electricity you pay for is actually doing work. We’ll cover detailed terms, calculations, and fixes later, but for now just know that it’s measured as a percentage and often conveyed as a decimal. For example, if 92% of your electricity is doing work, you’ll have a power factor of 0.92. The issue you’ll see is that a low power factor can cause many issues.

Low Power Factor

Although it varies, most electrical utilities want your facility to have a power factor of at least 0.90, although it often varies from 0.85 to 0.95. Whatever their threshold, if you’re below it you may have penalties added to your bill, and they’re not always clear. You may see lines you don’t understand and that can often be a power factor penalty.

The power factor issue is made worse by a disconnect we see on many sites. Often the person who pays or authorizes the power bill is not the person who is responsible for the electrical equipment. You may have a maintenance, electrical, or I&E team that handles the equipment, but accounting or AP pays the bills. In those cases, the people best poised to address power factor are unaware there’s an issue.

The utility cares for a few key reasons. First is that low power factor overloads transformers and conductors, shortening their life and lowering the number of customers they can serve. Low power factor leads to heat and losses, not just in utility equipment but in your own components inside the facility.

As a facility, there’s more financial incentives to improve power factor than just penalties. If only 50% of your power is doing work, meaning a power factor of 0.50, it doesn’t necessarily mean half your electricity is wasted, but it does mean you need much more current to deliver the same real work, which increases losses and demand charges. You also are likely to encounter the same reduced equipment lifespans the utility is worried about.

The Cost of Low Power Factor - An Example

Theoretical talk is good, but let’s look at the actual numbers. Let’s compare the numbers on what would be considered a low power factor (0.70) and a good power factor (0.95) to see what the difference in the bill would be.

Let’s use Rocky Mountain Power’s policy and start with an assumption of a facility that has on-peak demand of 1,000kW and uses 1,000,000kWh, half on-peak and half off-peak.

According to their policy, a power factor of 0.95 would have no penalty, so just the standard payment. They have a facilities charge, on-peak power charge, and energy charges, plus general fees. Running the math, you see a bill of $66,612 per month.

Rocky Mountain Power’s policy is that for each 1% below a 0.90, they increase the on-peak kW by 0.75%. That means that being 20% below the threshold adds a 15% increase to the on-peak kW.

When you run those numbers out, your new monthly bill is $69,046.50 per month because of an added penalty of $2,434.50. That’s a 3.7% increase in the entire bill.

This example hasn’t even considered the fact that your original power consumption was probably already higher because of low power factor, meaning more kWh you’re billed for. With low power factor, you’re purchasing more power than a comparable facility with good power factor, so your bill would be even higher. Although it isn’t typically a massive amount of additional energy use, every lost dollar that can be saved is important.

Add in that your equipment will often start to fail faster than normal, and you start to see the costs of power factor issues rising. That means that a potential return on investment (ROI) for fixing power factor can be significant.

The issue here? That penalty was built into the customers on-peak power charge and any additional power consumed because of low power factor just looks like high energy usage. That means a customer with this bill might not even know they’re paying a penalty without a careful analysis of the bill.

The Details of Power Factor

Because power factor is so important, it’s good to dive into the details that can make this confusing, as well as how to calculate what your power factor is. There are multiple ways to get your power factor and a few places you could get data. Looking at the kW vs. kVA on your electric bill can be helpful, but you may also be able to get the data with some clamp meters, power analyzers, drive parameter readouts, or even from an existing SCADA or PLC.

It's also important to note that there are technically two types of power factor:

- Displacement power factor - the current sine wave lags the voltage sine wave, which is lagging power factor. If current is leading voltage, you get leading power factor, which is also a form of displacement power factor. Displacement is the focus of this article.

- Distortion power factor - harmonics distort the waveform, which you can learn more about in our VFD Harmonic Mitigation article.

Your total true power factor is technically the combination of displacement power factor (phase shift) and distortion power factor (harmonics). We’ve addressed harmonics in other places so we’ll focus on displacement power factor here.

Real Power

The first term to know is real power, often shown as a “P” in equations. This is the part of your electricity that is making things move and happen. It’s “useful” and what you want to maximize. This is measured in kilowatts (kW).

Reactive Power

Next is reactive power, shown as a “Q” in equations. This is often called “wasted,” “lost,” or “non-working” power. Reactive power isn’t consumed like real power, but it sloshes back and forth between source and load causing heating and losses in your system. It’s what we’re trying to minimize. This is measured in kilovolt amperes reactive, or kVAR.

Apparent Power

The last important term is apparent power, written as “S” in equations. This is the total or demand power, which is what your utility has to supply to you. This is measured in kilovolt amperes, or kVA.

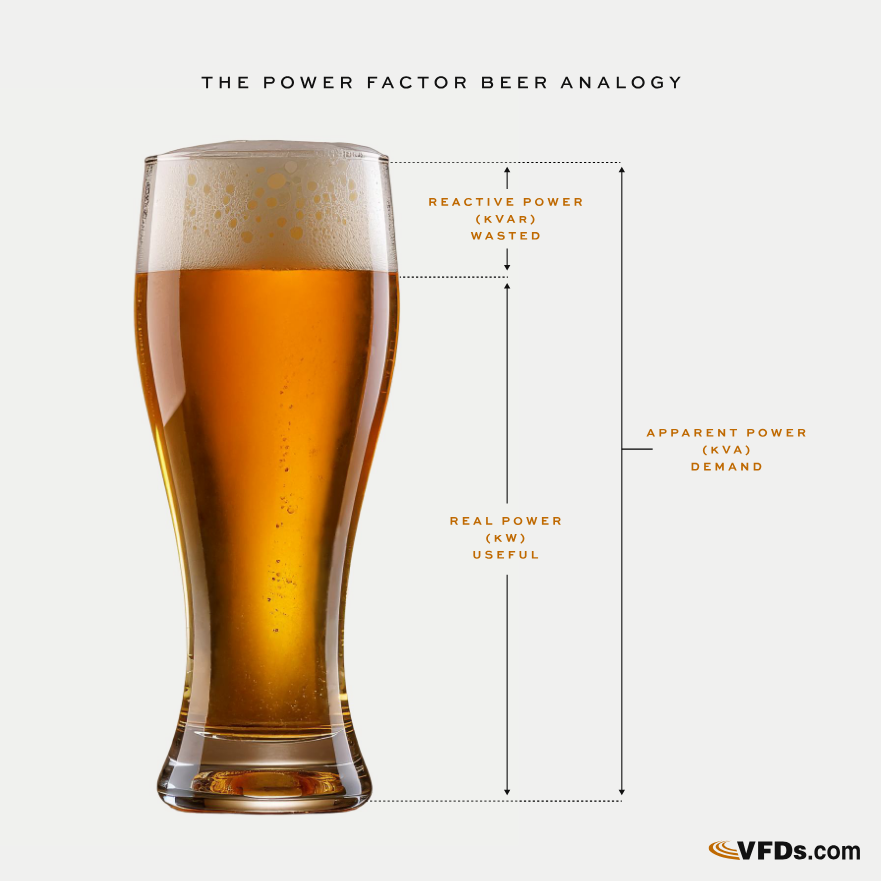

The Beer Example

Before we move on to the actual calculations, let’s talk about the most famous way to depict power factor: the beer example.

If you were to go to your local bar and ask for a pint of beer, you would pay for the full mug. In most cases, you don’t actually get a glass filled to the top with liquid beer. Some space is taken up by the foam head. Many connoisseurs will tell you this is important, but you wouldn’t want half of your glass taken up as wasted space. There’s a level where you would start to feel like you’re not really getting the beer you paid for.

This is the same situation with power factor. You pay for the full demand power (kVA) no matter what the makeup is in the glass. Ideally you want to maximize the good contents, either the beer or the “usable” power (kW), and minimize the bad contents, either the foam or the “wasted” power (kVAR).

The Power Factor Ratio

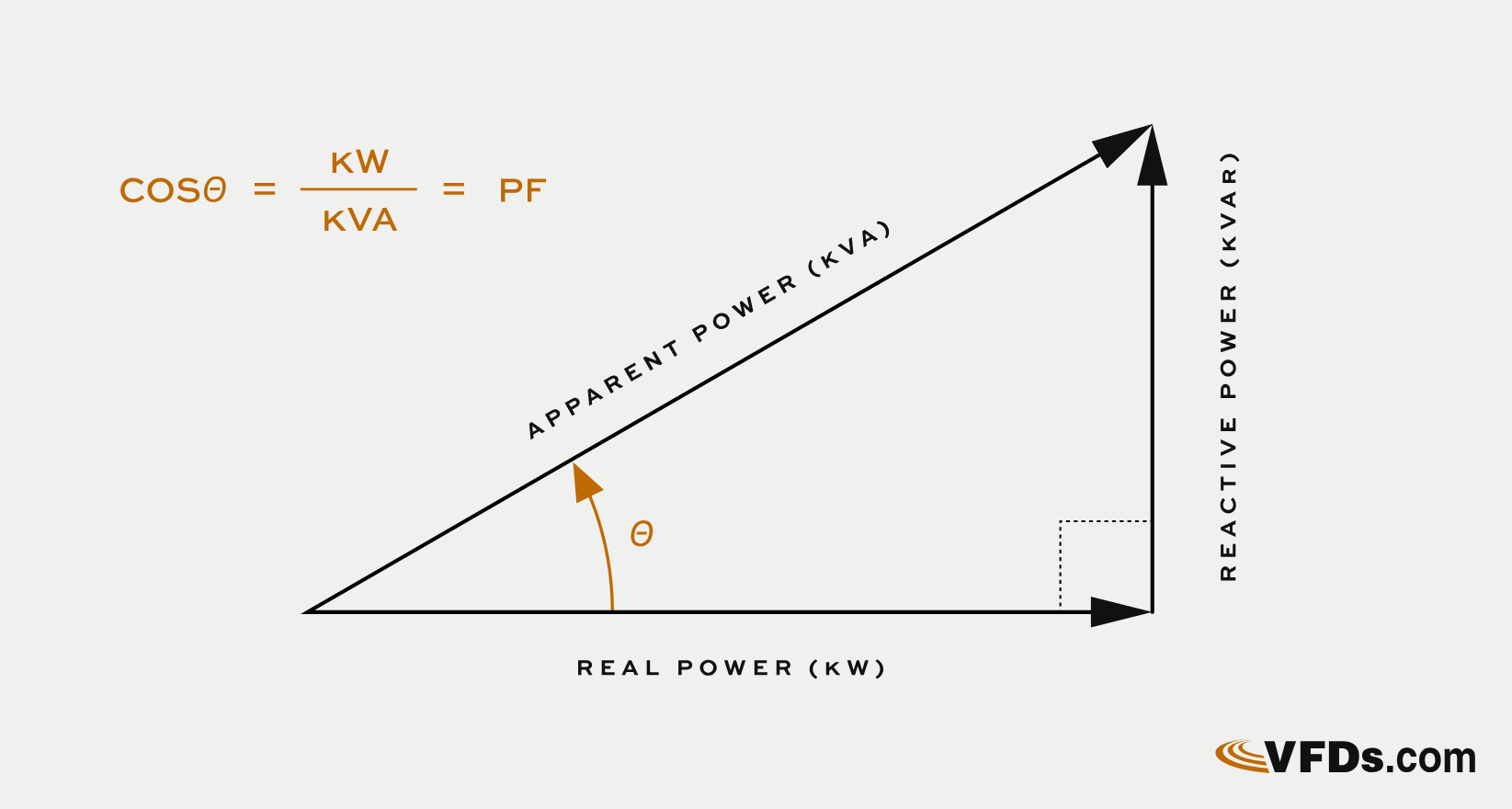

Now that we have the terms and a visual representation of each, let’s talk about the relationship. Power factor is a ratio, where real power is divided by apparent power.

PF = Real Power (P) / Apparent Power (S)

The relationship is not simple addition. kVA is not the total of kW and kVAR, it is the magnitude of the vector sum. That means the equation here is:

kVA2 = kW2 + kVAR2

This relationship can be shown in a graph like the one below. The power factor angle, shown as theta (Θ), is the cosine between the voltage and current. That means that:

PF = cos Θ

We now have multiple ways to get to the same number. You can either measure the phase angle or do the math based on real and apparent power. Based on whether you have access to a utility bill, monitors, or other data, you now have a way to find out your power factor.

Lagging and Leading Power Factor

When you run through the math, you’ll find you can get a few different power factors. If you were to have a perfect balance, where kVA = kW, you would have a power factor of 1.0, also called “unity” power factor.

The most common issue is where the current sine wave lags the voltage sine wave, which is lagging power factor.

If you overcorrect and add too much capacitance, you may think that you’ll see a power factor over 1.0. Your meter and many people in the industry will show you numbers like that, saying you have a power factor of 1.05 or something similar. This is a convenient way to communicate a leading power factor, but just remember that it’s mathematically impossible. Your kW can’t be higher than your kVA, so the number will always be 1.0 or less. If you’re told your power factor is 1.05, just know that technically what you have is a -0.95, where it’s 5% leading instead of lagging.

Lagging power factor is caused by inductive loads that require a magnetic field to operate. Leading power factor is caused by capacitive loads that store energy in electric fields.

Both are problems for your system. The rest of this article will deal with lagging power factor, but leading power factor has its own issues. It can create voltage instability, losses, and decreases equipment lifespans, especially on equipment like generator alternators, uninterruptible power supplies (UPS) and switchgear.

Causes of Lagging Power Factor

Bad power factor is most often caused by inductive loads like motors and transformers. Inductive loads require reactive power to magnetize, leading to “wasted” power. This is even worse when these are lightly loaded or idle as they don’t consume power for work but still draw reactive power.

Although motors and transformers are the main inductive loads causing problems, it’s possible to see the source being other loads like welding equipment or lighting. If these are common at your facility, evaluate these sources.

Systems also see problems from unbalanced three-phase loads. When too many single-phase loads are on one leg, there’s been random breaker assignments over the years, or you have other equipment failures like winding issues or bad connections, one phase may see a much higher load than the others. These issues force extra current to flow in the system without really working. That means you get more kVA, lower power factor, and extra heating that isn’t solved with solutions that add extra capacitance.

How to Fix Power Factor

If you’ve determined that bad power factor is a problem affecting you, it usually makes sense to address it from a financial, safety, and reliability standpoint. While some methods are more common, it turns out there’s quite a few ways to improve your power factor. Let’s cover the most common methods, as well as the pros and cons of each.

Capacitor Banks

There are multiple approaches to capacitor banks. Some decide to add one central point of power factor correction with a large capacitor bank centralized near the utility entrance. Others decide to tackle it throughout the facility with smaller capacitor banks.

The great part of a capacitor bank is its cost. They tend to be cost-effective ways to add capacitance to the system. They do come with some problems because of their simplicity.

First is that they may add too much capacitance, hurting generators, switchgear, and other equipment. They interact badly with harmonics and can cause resonance, and don’t often work well on lightly loaded inductive equipment. When caps switch on and off, they can also cause voltage sags and surges.

Capacitors are often the weak spot in an electrical system. They don’t last as long as other equipment, and when they fail it can be catastrophic. Capacitors are known to bulge, rupture, or explode as they fail, leading to other issues.

In short, capacitors are a good option for cheap, but they have plenty of drawbacks to consider.

Phase Advancers

Phase advancers are a niche technology, mainly used before VFDs and only compatible with slip-ring induction motors. These are typically considered obsolete at this point, with no real advantages over other technologies but plenty of drawbacks. If you have these, look at upgrading. If you don’t have these, they’re not worth considering.

The only situation where phase advancers are still used are on synchronous motors. By over-exciting the motor, you can add VARs back into the system. These cases tend to be niche and on the fringe for most systems, so talk to an expert if you have a synchronous motor and power factor issues to see if this is an option that will work for you.

Static Var Generator (SVG)

A static var generator (SVG) is a responsive, modern way to handle power factor. In many cases it is similar to an active harmonic filter, monitoring the system and using switching devices to add VARs, offsetting bad power factor. It does this in real time and can inject both leading and lagging current, handling both displacement and distortion power factor. These are easy to integrate in either a centralized or localized approach.

This solves many of the issues you see with capacitor banks. It avoids overcorrection, doesn’t have sags and surges, and needs relatively little maintenance, while more completely addressing power factor correction.

The downside is often cost. Any individual failure on a capacitor bank is often easy to replace with a low-cost capacitor, but an SVG is an entire unit that can be more expensive to replace. With targeted implementation, these can be a cost-effective way to handle poor power factor, but they can also be overkill for small problems.

Standard Variable Frequency Drives

There are very few cases where adding a variable frequency drive (VFD) is done simply for correcting power factor. VFDs make sense when you’re looking to add process control and save energy. A side benefit is that they also improve the power factor on a specific motor system. While they don’t correct your system as a whole, a standard low voltage VFD will raise the power factor of a system up to approximately a 0.96, at least on the displacement side.

The downsides are noticeable. This doesn’t correct other problems throughout the facility, just the motor system it’s on. They’re expensive as a power factor correction device as they have a lot of other functionality built in. They also introduce harmonics, which can lower your true power factor by introducing distortion. In general, a VFD should not be implemented to correct power factor, but it should be considered as part of a holistic approach to power factor correction when they’re already being considered for other reasons.

Active Front End VFDs

VFDs with an active front end (AFE) can maintain a unity power factor on their motor system. In some AFE designs, they’re able to use excess capacity to put VARs into the system and correct power factor throughout a facility. When there’s extra capacity, imagine these particular AFE designs as a VFD with an SVG built into it. Although that’s not the exact topology, it gives a good approximation of the capability.

The downside is cost, like many other technologies. In some cases where a VFD is already being added, the upgrade to an AFE is easy to justify based on the power factor costs it can save. This is especially true as active front end technology becomes more cost-competitive, especially driven by the use of SiC MOSFET technology, which is just starting to appear in the industry.

Just like with VFDs, this option doesn’t make sense unless a VFD is already being considered. In cases where a new VFD is being added, it’s worth considering upgrading to an active front end drive.

Replacing Old Motors

Sometimes the answer isn’t to add more technology but to improve the source of pollution. That can be the case with old motors and transformers. Older motors were often more robust, but that came at a cost. Older motors often have worse power factor and can be improved with a newer motor.

This makes even more sense when you have a situation where the motors should be replaced for other reasons, such as energy efficiency, reliability, or other upgrades.

Process Improvements and Other Technologies

Some other technologies can also help improve power factor. Harmonic filters can reduce distortion power factor but are typically added to meet harmonic requirements and aren’t considered for power factor. Some active harmonic filter (AHF) devices can fix both harmonics and power factor, but are typically not used unless harmonics also need to be addressed.

You also can change how you’re running your facility. Operate equipment at higher loads and avoid idling to make more of your power work instead of remaining reactive. Avoid overvoltage and evaluate single phase loads and damaged equipment.

| Technology | Simplified Explanation | Pros | Cons | |

| Traditional | Capacitor Bank | Cheap, traditional fix | Low cost, addresses majority of lagging power factor issues | Overcorrection, voltage sags & surges, resonance, interactions with harmonics |

| Phase Advancer | Obsolete solution | Has a use case for turning synchronous motors into PF correction devices | Older, obsolete technology | |

| Modern | Static Var Generator (SVG) | Modern electronic solution | Addresses leading and lagging power factor, avoid most issues of capacitor banks | Can be cost-prohibitive for small fixes |

| Active Harmonic Filters | Modern harmonic solution with some Power Factor correction capability | Often has ability built in when already used in the system | Typically expensive and ineffective if only used for Power Factor | |

| Load-Based | Variable Frequency Drive | Motor control with improved Power Factor | Other advanced features | Lots of unneeded functionality for pure Power Factor correction |

| Replacement Motors | Install motors with higher Power Factor | Reduces Power Factor at the source | May not improve Power Factor in every situation | |

| Process Improvements | Adjust loading and maintain electrical system best practices | Low cost and may not require new equipment | Requires expertise and may not address large Power Factor issues | |

Evaluate Your Power Factor

It’s not always easy to identify if you have a power factor problem. Our team is experienced at identifying and correcting these issues. You could be losing thousands of dollars a month while shortening the lifecycles of your equipment. Reach out to an expert today to start saving money and adding reliability.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is power factor?

Power factor is a ratio that shows how much of your total power is being used to work. The higher it is, the better your facility is doing.

How do you calculate power factor?

You calculate power factor by dividing your real “working” power by your total “demand” power. The answer is a percentage that is often communicated as a decimal, known as your power factor. You can also calculate this by determining the power factor angle, or the cosine between the current and voltage.

What is lagging power factor?

Lagging power factor is when the current waveform lags the voltage waveform, leading to a lot of reactive power that’s not working for you.

What is leading power factor?

Leading power factor is caused by too much capacitance, causing the current waveform to lead the voltage waveform.

What is displacement power factor?

Displacement power factor is when the current and voltage waveforms are offset by either extra inductance (for lagging power factor) or excess capacitance (for leading power factor).

What is distortion power factor?

Distortion power factor is a reduction in power factor caused by harmonics from nonlinear loads like VFDs, LED drivers, rectifiers, etc. Harmonics most often come from variable frequency drives (VFDs) in a system.

Is power factor correction a scam?

Power factor correction in residential settings is often a scam as residential users are typically not penalized for bad power factor. In commercial and industrial settings, poor power factor is very real and an important thing to correct.

What are the effects of bad power factor?

Bad power factor can cause premature equipment failure. It can also lead to extra electrical utility charges and penalties.

How do you correct bad power factor?

There are many approaches, but common methods to address power factor include capacitor banks and static var generators (SVGs). Other fixes like adding VFDs (standard or with active front ends) and replacing motors can also help.

Should I use a phase advancer?

Phase advancers are narrow in scope: they only work with slip-ring induction motors. You can fix power factor more effectively with other technologies, so they are typically considered obsolete.

What are the two types of power factor issues?

When someone refers to two types of power factor issues, it can refer to two different subjects. First is a leading vs. lagging power factor, depending on whether the current wave form is lagging the voltage or it’s reversed. It can also refer to displacement vs. distortion power factor, where displacement is excess inductance or capacitance and distortion is excess harmonics.

What is a capacitor bank?

A capacitor bank is an assembly of capacitors, often switched in steps, used to add capacitance in an attempt to fix lagging power factor.

Are there side effects with capacitor banks?

Capacitor banks can overcorrect and create a leading power factor. They can also cause electrical system issues like voltage sags and surges, resonance, and interactions with harmonics.

What are static var generators?

Static var generators, or SVGs, are an active way to solve power factor. They can correct both lagging and leading power factor, avoid overcorrection, and avoid many of the side effects of capacitor banks.